There is a constant steady stream of opinions that economic growth, and in particular, GDP per capita, is overrated and that it should be downplayed as a policy objective, mostly from people in the rich countries of the world (the OECD). My main point in the attached new (draft) paper is that priorities depend not just on what you want, but how much of what you want you already have. What makes the rich countries rich is that they currently have very high levels of GDPPC, and, given that they have a lot, they might, at the margin, want to value other things they also want they have less of.

But it is a huge, huge, mistake to think that priorities are just preferences and countries with low GDPPC, even if they want exactly what countries and people in the OECD want as preferences, might have a very strong priority for more economic growth as they have so little now.

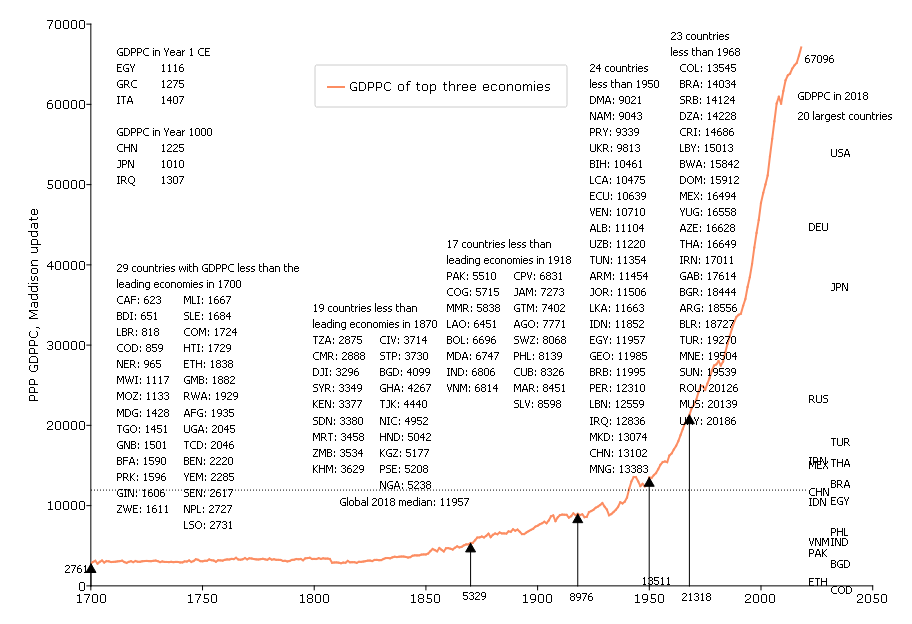

There are two key graphs. One, from a previous paper of mine, is just a graph built on the (updated) Maddison-style estimates of long run GDPPC (Bolt and Van Zanden 2020). This shows the evolution of the GDPPC of the leading three countries in GDPPC (whichever they were) from 1700 to 2018. The point of this graph (which is a variant on the “hockey stick” graphs that illustrate the consequences of the acceleration of economic growth that began sometime in the 19th century and has been sustained in the OECD countries at roughly 2 ppa) is that many countries in the world today are still at levels of GDPPC that the now advanced countries had a century or more ago. Twenty nine countries had GDPPC in 2018 lower than the most advanced countries had in 1700. Another nineteen countries have GDPPC lower than the leading countries had in 1870.

And the poorer countries in the world today are not that much higher than the GDPPC that the leading countries had 2000 or 1000 years ago. Niger is estimated to have lower GDPPC in 2018 than Egypt has in 1 CE. Ethiopia’s GDPPC, at M$1838 (M$ for the Maddison PPP units) is only about 50 percent above where China was in 1000 CE.

This is just important factual context as it is obviously one thing to debate how much a priority economic growth is when GDPPC is M$40,000 or more (Japan, Germany (DEU), USA) than if one is at the levels of India or Vietnam (M$6800) or less. Even China or Indonesia, countries that have obviously had extended periods of rapid growth are still only at the level the leading countries had in 1950. Clearly how much more economic growth is a priority depends on how much one has had.

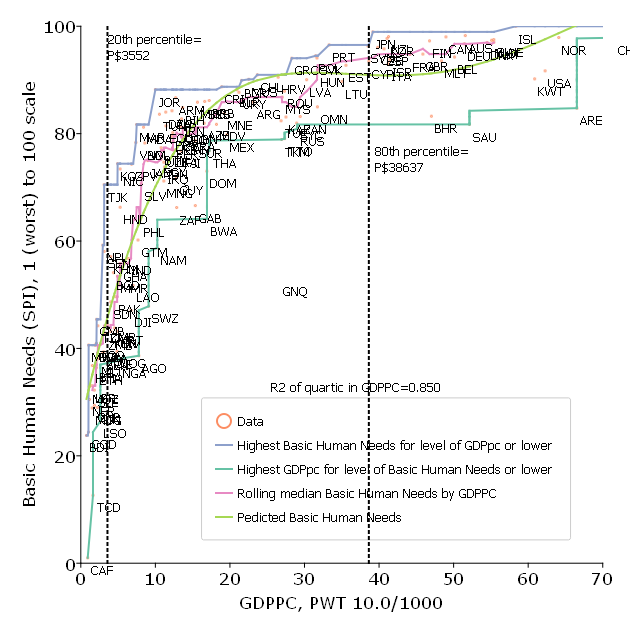

The second key graph, and the key point of the paper, is that if one constructs any index of the basics of human material wellbeing not from economic output measures but from physical indicators like health, education, water and sanitation, nutrition, environment it is very tightly associated with GDPPC in a non-linear way. As countries move from low levels of GDPPC to levels up to about P$ 25,000 (about where Argentina and Chile are) the extent to which basic human needs are met increases very steeply. After that, and in particular for the top quartile of countries (above P$38,637, where P$ is the Penn World Tables PPP measure) there is little gain to basics–because the level of basics is very high.

And what the paper demonstrates at some length is that this strong, non-linear association of GDPPC and basics is robust to any plausible definition of “basics.” That is, if one constructs a multi-dimensional measure of basics of human wellbeing it doesn’t really matter which exact variables one includes or the weights one uses to add the indicators up, you get roughly the same results. So the claim is not that GDPPC and “a” measure of basics are related strongly and non-linearly, the claim is that this is true of “any” measure of basics.

The reason I wrote this paper is not that I want to weigh in about what priority should be placed on economic growth in the USA or Germany or New Zealand or the UK. they have a lot of it. But my worry is that the Golden Rule, that one should “do unto others as you want have them do unto you” can be confused between “preferences” and “priorities.” The debate about what development agencies like the World Bank or IADB or the bilateral development agencies of OECD countries might be influenced by thoughts of the type “Since we want in our own domestic affairs a lower priority on economic growth, development agencies should put less weight on economic growth.” But the Golden Rule has to be applied by asking “what would I want if I had my preferences and a given set of circumstances, like how much I already have of the various things I want.”

As we know from Engel’s law, when people have low levels of income their share of spending on food is very high (70 percent or more) and when people have very high levels of income their sharing of spending on food is more like 7 percent. This is not because preferences change but because priorities change and when one gets more food it becomes, at the margin, less of a priority. But obviously the Golden Rule conclusion for a rich person is not “since food is not a priority for me it is not a priority for others so I won’t worry about food consumption as a priority.”

This is part of a broader argument of mine that we need to keep economic growth (“gold”) in the Golden Rule of what development agencies see as their role to help poorer countries (and societies and households) achieve the levels of economic productivity that are essential to provide their populations with the basics–even if that, thankfully, is no longer a priority for prosperous places.

Here is the draft paper (revised May 22, 2022).