What’s the big idea? Most of my research and writing on the issue of labor mobility has been devoted to documenting the huge potential income gains to low skill migrants moving from low income to high income countries. This increased mobility is blocked by rich country politics–in spite of the fact that, because of demographic changes, the rich countries actually need–and will increasingly need–migrants.

My main co-author and collaborator on this topic has been Michael Clemens of Center for Global Development, who is doing great research on this topic.

Let Their People Come: Breaking the Deadlock in International Labor Mobility. Center for Global Development: Brookings Institution Press, 2006.

“The Place Premium: Bounding the Price Equivalent of Migration Barriers.” (Review of Economics and Statistics, on-line November 2018). (with Michael Clemens and Claudio Montenegro). (earlier version, CGD working paper #428).

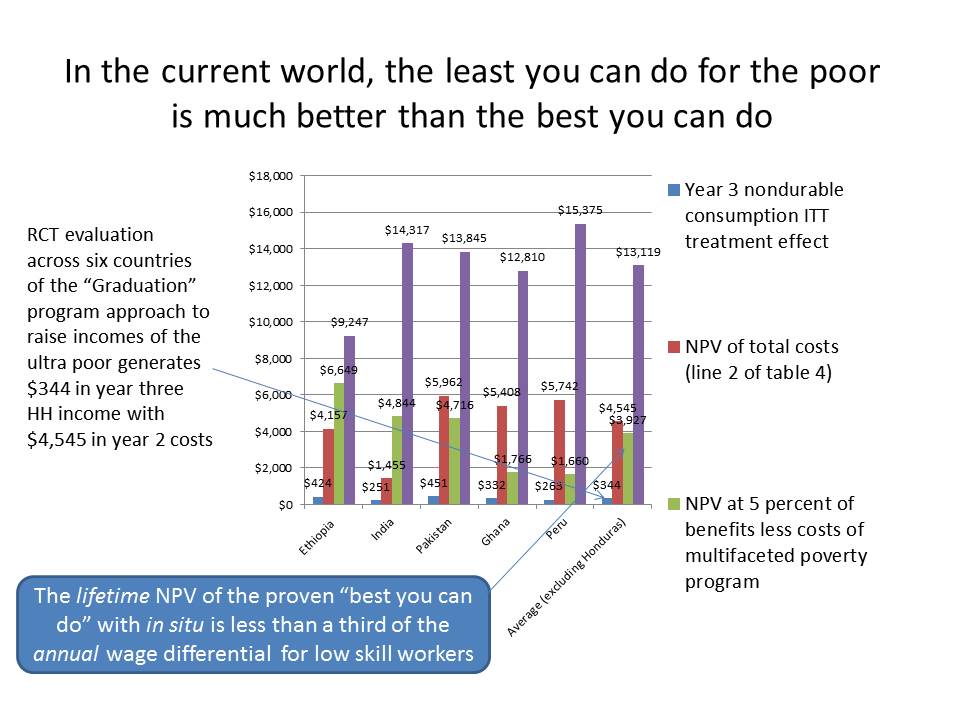

Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct Assistance, and Economic Growth – Working Paper 479. March 20, 2018. This is a blog on this paper. This is based on a speech presented on November 27, 2017 as part of the 2017–2018 lecture series, “A 21st Century Immigration Policy for the West,” co-sponsored by Reason Foundation and Michigan State University’s Symposium on Science, Reason and Modern Democracy and will appear in a forthcoming volume.

The key point is that “the least you can do for the world’s poor is better than the best you can do“–that is, the “least you can do” is just let people work in your country because it costs you nothing and the “best you can do” with in situ targeted anti-poverty programs is about cash.

I gave several presentations in the fall of 2018 on the argument for reductions in the barriers to low-skill labor mobility as an anti-poverty measure. At the Graduate Institute in Geneva, a lecture to the MPP students at Blavatnik School of Government, at the Global Priorities Institute.

“The New Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment.” 2018. (forthcoming in Journal of Development Economics). with Michael Clemens. This paper addresses the new argument that the gains from migration are overstated because migrants lower TFP (“A”) in the country they come to (arguments suggested by George Borjas and Paul Collier, for instance). We build and empirically calibrate a model with these “epidemiological” features that allow the possibility of thresholds above which migration reduces TFP. We argue that, even taking into account these arguments, at the current levels the flow rates of migration are factor multiples lower than the income maximizing optimum. So these arguments, even if logically valid and possible descriptions of a possible state of some economy do not appear to be relevant at the margin to OECD countries today.

One big issue that is, I feel, under-addressed in the current literature is the bias created for labor-saving technological change by barriers to labor mobility. Why are geniuses destroying jobs in Uganda? Everyone (left and right) can agree that if carbon is under-priced due to market failures then this creates too little incentive for the market to do research, discover, innovate, and market lower carbon technologies. Border based barriers to labor mobility create the opposite perverse incentive–people are investing in low-skill labor saving technologies (like self-driving trucks) even though this is a globally abundant factor.

A theme of my 2006 book was that “irresistible forces” meet “immovable ideas.” One of the “irresistible forces” leading to greater pressures for labor mobility is the rapid demographic shifts in Europe and Japan that have produced ageing populations (“Why Demographic Suicide: The Puzzles of European Fertility“) is Europe Committing Demographic Suicide”). I argue that while the “refugee crisis” was about Europe’s ability to accept migration, in fact Europe would need about six million movers a year–212 million more people–between now and 2050 just to keep its ratio of labor force aged to retiree aged population constant–because each new retiree aged person needs 3 workers and so the ageing of Europe means they need more workers, but the demographic shift means there will be less.

“Income Per Natural: Measuring Development for People not Places.” Population and Development Review, vol. 34 no.3, 2008. (with Michael Clemens).

“The Future of Migration: Irresistible Forces Meet Immovable Ideas.” 2008. in The Future of Globalization: Explorations in Light of Recent Turbulence. Ernesto Zedillo ed., 2008.