I have a new draft paper drafted as a handbook volume on “Development and Aid” being edited by Shanta Devarajan, Jennifer Tobin, and Raj Desai at Georgetown. The paper kind of builds on an earlier blog of mine The Perils of Partial Attribution in which I worry that people sometimes get confused about the facts and the counter-factual. The title of the paper is: “Development Happened. Did Aid Help?” (This is the version as of February 2024).

An organizing analogy is the Belichick-Brady debate. The fact is that the team they were both affiliated with, the New England Patriots, had one of the most impressive and successful periods of any major sports franchise, ever, winning 6 Super Bowls. One then might want to parse out some causal attribution of how much of this success was due to Bill Belichick as coach and how much was due to Tom Brady as quarterback. And so on imagines an alternative world in which Tom Brady had played for another team with an average (sequence of) coaches or that Bill Belichick had coached with a sequence of quarterbacks.

The difficulty with the development-aid debate outside of the realm of development experts is that, as Hans Rosling so gently puts it, the “person on the street” in a rich country knows less about conditions in developing countries than a monkey, because at least a monkey doesn’t know stuff that is wrong.

Something like 85 percent of Americans thought global poverty over recent decades had either “stayed about the same” or “risen.” This is like trying to engage in the Brady-Belichick debate with someone who says “Well, we know neither can be so terrific because their team never won a Super Bowl.” Well, no, that is actually not up for debate as that is a fact, a given, something that everyone agrees actually happened. The only question is what causally explains that fact.

If you believe, wrongly, that “development didn’t happen” then it is easy to think “well, since ‘aid’ was supposed to promote development and development didn’t happen, aid (probably) didn’t work.” The conclusion is not necessary wrong, but the argument is just stupid because it starts from demonstrably incorrect assumptions about the facts.

Let’s not start the discussion of development success with economic indicators (like GDP per capita growth) as they are controversial and let’s not start with poverty, as that has so many definitions. Let’s start with a couple of things that pretty much everyone agrees with: that every child should go to school and that it is bad when children die. Turns out in the “development era” progress on those was amazingly fast.

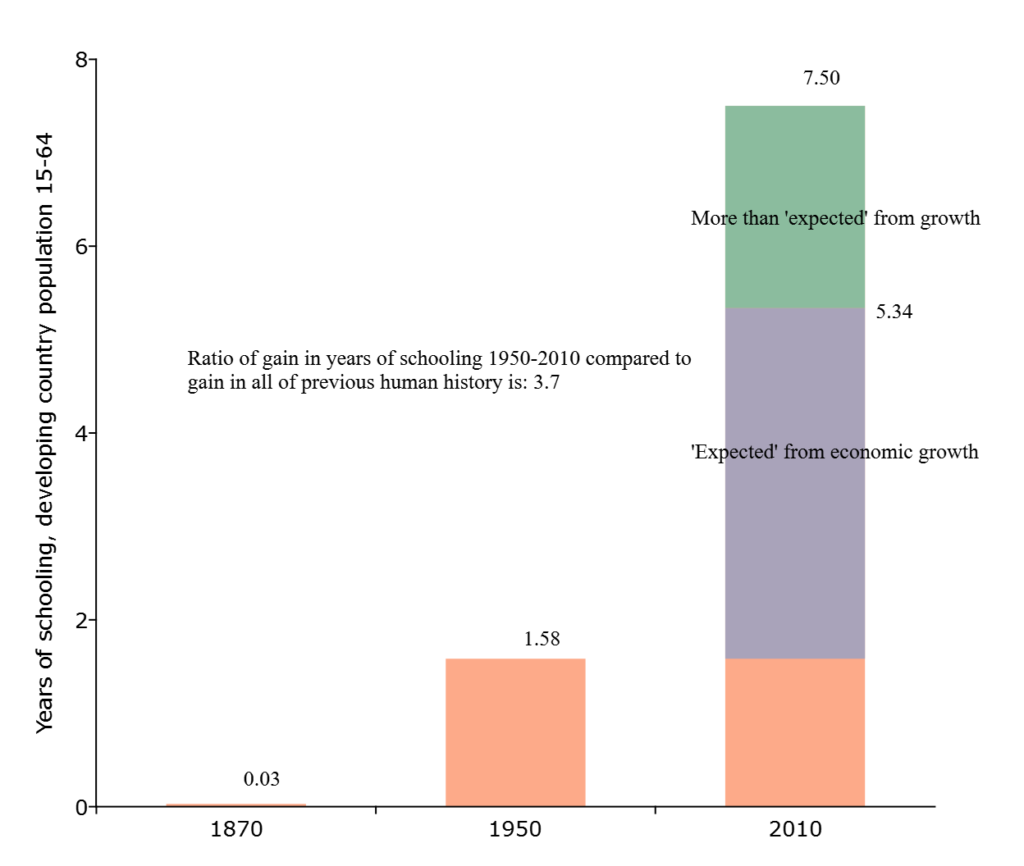

The figure shows the average years of schooling of the adult population in the developing world in 1870, 1950 and 2010 (from Lee and Lee 2016 data). From all of human history to 1950 (however many thousands of years you want to call that) the cumulated gain in years of schooling in formal education was 1.58, with most people having had no schooling at all. By 2010 the average was 7.5 years, so that there was more gain in years of schooling in the sixty years from 1950 to 2010 than in all previous human history, by a factor of 3.7.

I am not saying that everything about this expansion of education was a success, and I am a big advocate of acknowledging and addressing the “learning crisis” that lots of kids are getting schooling with little or not learning, but still, this is a massive, historically transformative success to have moved from little or no schooling to pretty much universal access to primary schools in pretty much every country. Big win. Huge win.

And, as an interesting dimension of that expansion of schooling, one can run a simple bivariate regression of years of schooling on GDPPC in 1950 and then “predict” the level of schooling that would have resulting from economic growth alone, and, contrary to the idea that “development” focused on growth but not human development indicators, here the progress in years of schooling was substantially more than growth would have “predicted” not less.

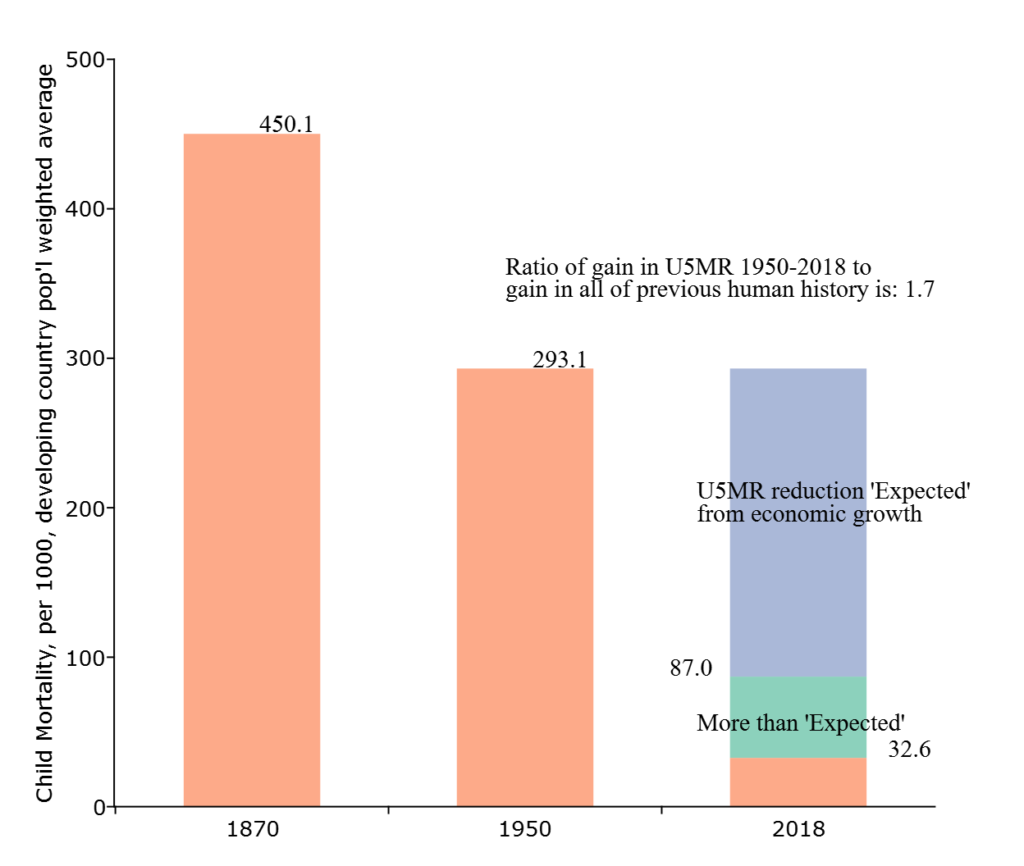

Same things are true of child mortality. Under 5 child mortality (deaths per 1000 births) fell from 293 in 1950 to 32.6 in 2018 (using data from Gapminder). Again, more reduction in child deaths from 1950 to 2018 than in all of previous human history, by a factor of about 1.7. Big win. Huge win.

So the question has to be: “What accounts for this enormous progress in a wide array of indicators of human wellbeing in the developing world in the development era?” It may be that aid played no role (or that it is just impossible to know with any confidence what role aid played as the right counter-factual just does not exist–as one suspects is the inevitable outcome of the Brady-Belichick debate) but at least let’s be smarter than monkeys about the actual facts that we are trying to understand and parse the causes of.