What’s the big idea? Most of my research and writing on the issue of labor mobility has been devoted to documenting the huge potential income gains to low skill migrants moving from low income to high income countries. This increased mobility is blocked by rich country politics–in spite of the fact that, because of demographic changes, the rich countries actually need–and will increasingly need–migrants.

In 2020 I co-founded Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP) with Rebekah Smith. She is the the Executive Director while I am the Research Director.

My main co-author and collaborator on this topic has been Michael Clemens at George Mason University who does great research on this topic (maybe better without me).

Let Their People Come: Breaking the Deadlock in International Labor Mobility. Center for Global Development: Brookings Institution Press, 2006.

Rotational labor mobility is the biggest global economic opportunity. This is a draft paper estimating the demographic needs of rich countries that can be filled with rotational labor mobility. The “base case” estimate is that rotational labor mobility for core skill workers into the demographic dearth of rich countries could lead by 2050 to 6 trillion in wage gains, accruing mostly to workers from youth bulge regions (Africa and South Asia).

“People over Robots: The World Needs Immigration before Automation.” Foreign Affairs, March/April 2023. This paper addresses a big issue that is, I feel, under-addressed in the current literature: the bias created for labor-saving technological change by barriers to labor mobility which make labor artificially scarce. I raised this in Why are geniuses destroying jobs in Uganda? which points out the irony that the richest people in the world are trying to eliminate jobs that a billion people on the planet would love to have, but cannot due to policy.

The idea that distorted relative prices produce distorted technological innovation is widely accepted. For instance, everyone (left and right) can agree that if carbon is under-priced due to market failures (the externality of the damage of carbon emissions) then this creates too little incentive for the market to do research, discover, innovate, and market lower carbon technologies. This has led to massive attempts to remedy this distortion and fund carbon saving technologies.

Border based barriers to labor mobility create exactly the same distortion, but in the opposite direction–people are investing in low-skill labor saving technologies (like self-driving trucks) even though labor is a globally abundant factor. This blog, Choose People, uses the example of the distorted incentives of the sugar quota in the USA to illustrate the potential for profitable but silly innovation.

“The political acceptability of time-limited labor mobility: Five levers opening the Overton window.” Public Affairs Quarterly, July 2023, 37(3).

“The Future of Jobs is Facing One, Maybe Two, of the Biggest Price Distortions Ever.” Middle East Development Journal, 12(1),June 2020.

“The Economics of International Wage Differences and Migration.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. (with Farah Hani). July 2020.

“The Place Premium: Bounding the Price Equivalent of Migration Barriers.” (Review of Economics and Statistics, on-line November 2018). (with Michael Clemens and Claudio Montenegro). (earlier version, CGD working paper #428).

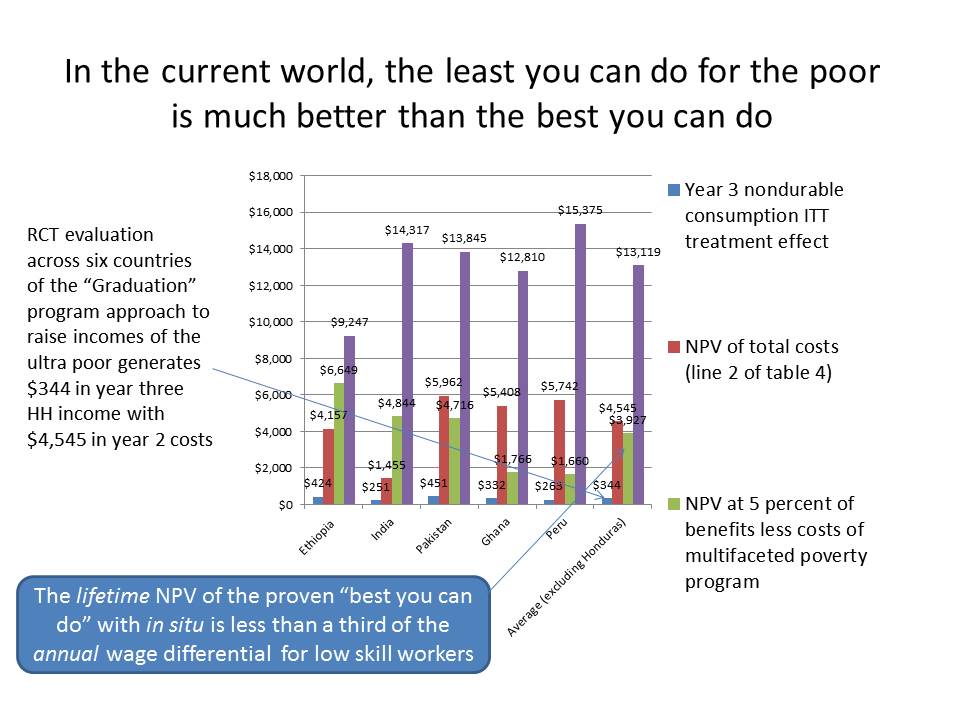

Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct Assistance, and Economic Growth – Working Paper 479. March 20, 2018. This is based on a speech presented on November 27, 2017 as part of the 2017–2018 lecture series, “A 21st Century Immigration Policy for the West,” co-sponsored by Reason Foundation and Michigan State University’s Symposium on Science, Reason and Modern Democracy. Here a blog on this paper.

The key point of this paper that “the least you can do for the world’s poor is better than the best you can do“–that is, the “least you can do” is just let people work in your country because it costs you nothing and the “best you can do” with in situ targeted anti-poverty programs is about the same cash transfers.

I gave several presentations in the fall of 2018 on the argument for reductions in the barriers to low-skill labor mobility as an anti-poverty measure. At the Graduate Institute in Geneva, a lecture to the MPP students at Blavatnik School of Government, at the Global Priorities Institute.

The New Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment.” Journal of Development Economics. 138(c). 2018. (with Michael Clemens).. This paper addresses the new argument that the gains from migration are overstated because migrants lower TFP (or “A” in the Solow model) in the country they come to (arguments suggested by George Borjas and Paul Collier, for instance). We build and empirically calibrate a model with these “epidemiological” features that allow the possibility of thresholds above which migration reduces TFP. We argue that, even taking into account these arguments, at the current levels the flow rates of migration are factor multiples lower than the income maximizing optimum. So these arguments, even if logically valid and possible descriptions of a possible state of some economy do not appear to be relevant at the margin to OECD countries today.

A theme of my 2006 book was that “irresistible forces” meet “immovable ideas.” One of the “irresistible forces” leading to greater pressures for labor mobility is the rapid demographic shifts in Europe and Japan that have produced ageing populations (“Why Demographic Suicide: The Puzzles of European Fertility“) is Europe Committing Demographic Suicide”). I argue that while the “refugee crisis” was about Europe’s ability to accept migration, in fact Europe would need about six million movers a year–212 million more people–between now and 2050 just to keep its ratio of labor force aged to retiree aged population constant–because each new retiree aged person needs 3 workers and so the ageing of Europe means they need more workers, but the demographic shift means there will be less.

“Income Per Natural: Measuring Development for People not Places.” Population and Development Review, vol. 34 no.3, 2008. (with Michael Clemens).

“The Future of Migration: Irresistible Forces Meet Immovable Ideas.” 2008. in The Future of Globalization: Explorations in Light of Recent Turbulence. Ernesto Zedillo ed., 2008.